On October 7, 2020, the anniversary of "Yahweh ben Yahweh Day" in Miami, originally proclaimed in 1990, brought renewed attention to the controversial legacy of Yahweh ben Yahweh, born Hulon Mitchell Jr., and his Nation of Yahweh. This date, once a celebration of a charismatic religious leader, now serves as a reminder of a complex and dark chapter in Miami’s history, marked by community revitalization, racial separatism, and violent crimes. This post delves into the history of Yahweh ben Yahweh, his rise to prominence, the establishment of his cult, the crimes that led to his downfall, and the lingering impact of his movement in Miami and beyond.

Early Life and Transformation

Yahweh ben Yahweh was born Hulon Mitchell Jr. on October 27, 1935, in Kingfisher, Oklahoma, the eldest of 15 children in a religious family. His father, Hulon Mitchell Sr., was a Pentecostal minister, and his mother, Pearl O. Mitchell, was a pianist for their church. Growing up in Enid, Oklahoma, Mitchell was steeped in religious tradition, singing in the church choir alongside his siblings, one of whom, Leona Mitchell, later became a renowned soprano at the Metropolitan Opera.

Mitchell’s early life was marked by intellectual promise and ambition. He studied psychology at Phillips College, an all-Black institution in Oklahoma, and later pursued law at the University of Oklahoma, though he did not complete a degree. After serving in the Air Force, he moved to Atlanta in the 1960s, where he joined the Nation of Islam (NOI), adopting the name Hulon X. His time with the NOI exposed him to Black nationalist ideologies, but he left the organization in the late 1960s, disillusioned. He then styled himself as a faith-healing Christian preacher, taking names like Father Mitchell, Brother Love, and Ock Moshe, drawing inspiration from early 20th-century African-American ministers like Father Divine.

In 1978, Mitchell arrived in Miami, a city reeling from racial tensions, particularly after the 1980 Liberty City riots sparked by the acquittal of white police officers in the death of Black insurance agent Arthur McDuffie. Adopting the name Yahweh ben Yahweh, meaning "God, son of God" in Hebrew, he declared himself a Black messiah and founded the Nation of Yahweh, a religious movement blending elements of Black Hebrew Israelite beliefs, Black supremacy, and his own apocalyptic theology.

Rise of the Nation of Yahweh

The Nation of Yahweh, established in 1979 with its headquarters in Miami’s Liberty City, quickly gained traction in a community desperate for hope and leadership. Mitchell’s doctrine posited that Black people were the true Israelites, descendants of the biblical tribe of Judah, and that whites and Jews were "infidels" and "white devils" responsible for Black oppression. He preached that Jesus was Black and that he, as Yahweh ben Yahweh, was the divine son of God sent to lead his people to salvation. His teachings emphasized Black pride, economic empowerment, and strict separatism, appealing to a population frustrated by systemic racism.

The Nation of Yahweh presented itself as a force for good, focusing on community revitalization. Members, who adopted the surname "Israel" and wore white robes and turbans, lived communally in the "Temple of Love," a 15,000-square-foot warehouse in Liberty City. They operated businesses, including motels, restaurants, and supermarkets, and renovated blighted properties, earning praise for reducing crime and drug activity in neglected neighborhoods. By 1990, the group’s real estate empire was valued at $8 million to $100 million, depending on estimates, and claimed thousands of followers across 45 cities.

Mitchell’s charisma and business acumen won him favor with local leaders. In 1987, T. Willard Fair of the Miami Urban League awarded him the Whitney M. Young humanitarian award. On October 7, 1990, then-Miami Mayor Xavier Suarez proclaimed "Yahweh ben Yahweh Day," citing Mitchell’s contributions to the city. This recognition, however, came just one month before his arrest, highlighting the stark contrast between his public image and the violent undercurrents of his organization.

The Dark Side: Violence and Control

Behind the facade of community upliftment, the Nation of Yahweh operated as a cult, with Mitchell exerting absolute control over his followers. Members faced strict rules, including 18-hour workdays, limited meals, and communal living conditions with no personal possessions. Women were subordinate, and some were allegedly coerced into sexual relationships with Mitchell. To join the inner circle, known as the "Brotherhood" or "Death Angels," members reportedly had to prove their loyalty by killing a "white devil" and presenting body parts, such as ears, as proof.

The group’s violent activities began to surface in the early 1980s. In 1981, Aston Green, a dissident member, was found beheaded in the Everglades, and his roommates, Carleton Carey and Mildred Banks, were attacked; Carey was killed, and Banks survived severe injuries. In 1986, the Yahwehs were linked to a firebombing in Delray Beach and the murder of two tenants during a takeover of an Opa-locka apartment complex. These incidents, among others, drew the attention of local police and the FBI.

The turning point came with the testimony of Robert Rozier, a former professional football player and Yahweh follower. Arrested in 1986 near the Opa-locka murder scene, Rozier admitted to committing multiple killings under Mitchell’s orders, including targeting random white people as acts of racial retribution. His testimony, though controversial due to his plea deal, was pivotal in building a case against the Nation of Yahweh. Former members, including Mitchell’s sister and nephew, also testified about beatings, murders, and Mitchell’s orders to eliminate dissenters.

Legal Downfall and Aftermath

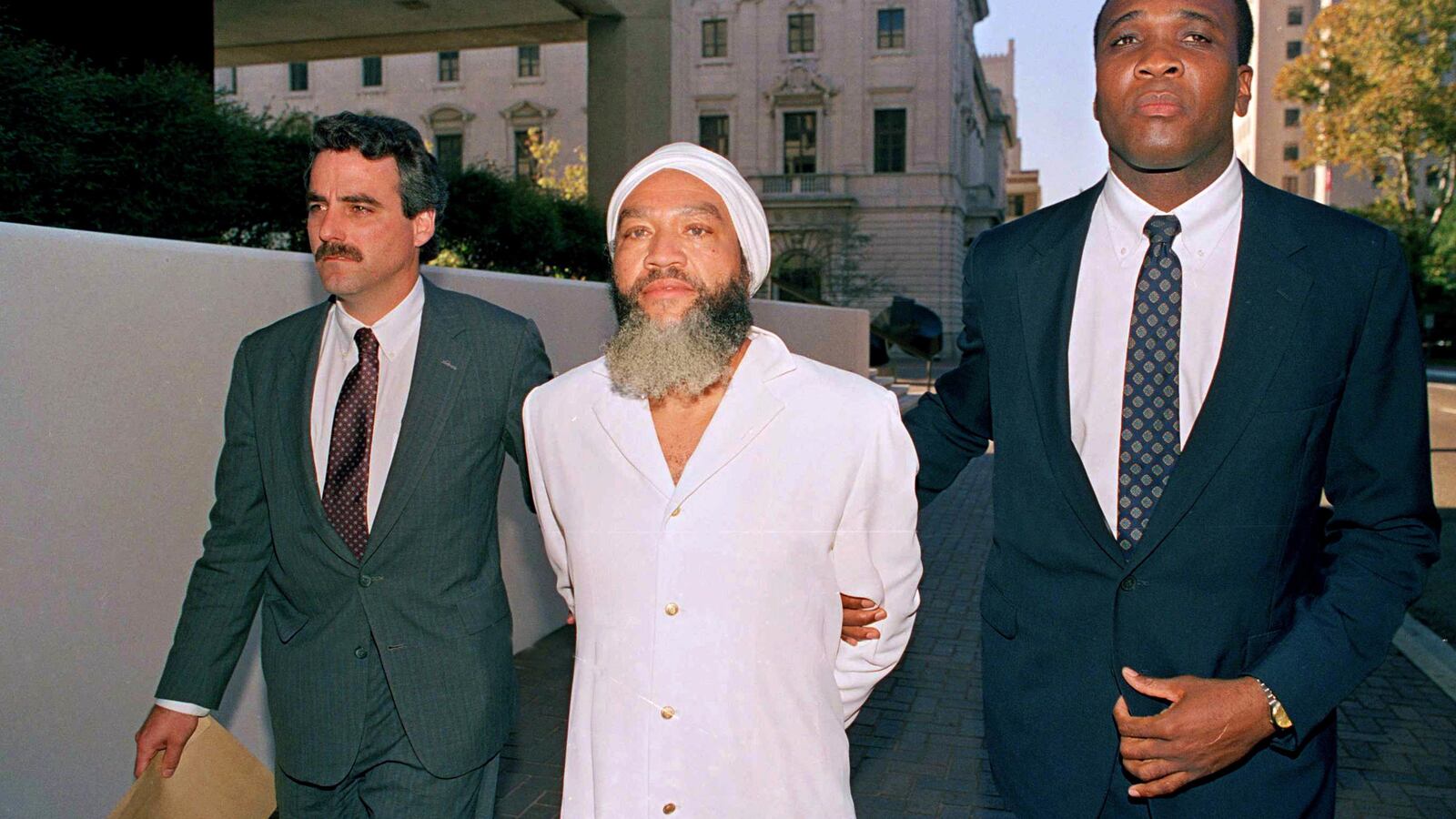

On November 7, 1990, just one month after "Yahweh ben Yahweh Day," Mitchell and 15 followers were indicted on federal racketeering charges, accused of 14 murders, two attempted murders, extortion, and arson. The FBI conducted simultaneous raids on 15 Yahweh properties in Miami-Dade County, arresting Mitchell in New Orleans. The indictment detailed a "reign of terror" in South Florida, with Mitchell allegedly ordering killings to maintain discipline and expand his empire.

In 1992, after a five-month trial, Mitchell and six followers were convicted of conspiracy to commit murder, though he was acquitted of racketeering and state murder charges. He was sentenced to 18 years in federal prison. The trial exposed the extent of the group’s violence, with testimony about beheadings, mutilations, and brutal punishments in the "Room of Understanding," a torture chamber within the Temple of Love.

Mitchell was paroled in 2001 but was barred from contacting his congregation. As his health declined due to prostate cancer, his attorney, Jayne Weintraub, successfully petitioned for his release from parole in 2006, allowing him to "die with dignity." He passed away on May 7, 2007, at age 71 in Opa-locka. His death was mourned by followers at a lavish funeral attended by nearly 500 white-clad members, signaling the group’s persistence.

Legacy and Continued Presence

By 2020, the Nation of Yahweh had faded from its 1980s prominence but remained active. The group’s website, continued to promote Mitchell’s teachings, and followers maintained a presence in Miami, including the Tabernacle of Shiloh Hebrew Israelite Witnesses Congregation in El Portal. The Southern Poverty Law Center classifies the Nation of Yahweh as a Black supremacist cult, noting its toned-down rhetoric but persistent antisemitic and separatist ideology.

The anniversary of "Yahweh ben Yahweh Day" in 2020, as highlighted by outlets like Miami New Times, served as a moment to reflect on Miami’s complex history with the Nation of Yahweh. The group’s early community efforts, such as cleaning up drug-infested areas, contrasted sharply with its violent crimes, leaving a polarized legacy. Some former members, like Khalil Amani, who became an FBI informant, have spoken out about the cult’s predatory nature, while others, including Mitchell’s daughter, defend him as a victim of a government conspiracy.

The story of Yahweh ben Yahweh also underscores broader themes of charisma, control, and the vulnerability of communities in crisis. As cult expert Rick Ross noted, groups like the Nation of Yahweh exploit people’s desires for belonging and purpose, gradually normalizing extreme behaviors. Miami’s racial tensions in the 1980s provided fertile ground for Mitchell’s message, and his ability to blend empowerment with violence made him a uniquely dangerous figure.

Cultural and Historical Context

The Nation of Yahweh’s iconography, such as the Black Madonna on Mitchell’s desk, reflects a broader cultural phenomenon of creolization, where religious symbols are adapted to local contexts. Art historian Jacek J. Kolasinski notes that the Black Madonna, linked to Haitian Vodou’s Ezili Dantó, resonated with Miami’s Haitian community, illustrating how Mitchell co-opted diverse spiritual traditions to bolster his authority.

The group’s influence persists in figures like Michael the Black Man (Maurice Woodside), a former Yahweh member turned conservative activist, who has defended Mitchell’s teachings while gaining attention for his political activities. This continuity highlights the enduring appeal of Black Hebrew Israelite ideologies in certain communities, even as mainstream Miami has largely moved on from the era of Yahweh ben Yahweh.

"Yahweh ben Yahweh Day" in 2020 was less a celebration than a historical marker, prompting reflection on a man who was both a community savior and a cult leader responsible for heinous crimes. Hulon Mitchell Jr.’s transformation into Yahweh ben Yahweh captivated thousands, offering a vision of Black empowerment that masked a violent agenda. His story is a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked charisma and the fine line between leadership and manipulation. As Miami continues to grapple with its past, the legacy of the Nation of Yahweh remains a haunting reminder of how hope can be twisted into horror.